Barclays: Reshoring Claims Exported by Morrison (Part 1)

The following analysis was originally published in the American Bar Association’s Litigation Section on Nov. 4, 2025. The article is now being reprinted in two parts, with Part 1 examining the recent recovery landscape for U.S. class actions with ADR claims and non-U.S. recoveries.

The Supreme Court decision in Morrison v. National Australia Bank, 561 U.S. 247 (2010), pushed out of the U.S. federal courts securities law claims brought by non-U.S. investors based on trading of non-U.S. instruments on non-U.S. exchanges. As a result, in the 15 years since Morrison, we’ve seen foreign investors bring shareholder recovery efforts in more than two dozen countries. To date, the results have been mixed, with most courts outside the U.S. proving poor alternative venues for such claims.

The June 24, 2025, decision in Merritt v. Barclays PLC, 2025 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 120796 (C.D. Cal. July 10, 2025), suggests a blueprint for reshoring claims exported by Morrison. It requires courts being willing to assert supplemental jurisdiction over foreign law claims in U.S. class actions following corporate scandals that trigger federal securities law claims brought by investors in U.S. exchange-traded instruments.

This article examines why the Barclays court asserted supplemental authority over United Kingdom (U.K.) securities law claims. It then reviews both historical U.S. class actions with similar profiles and non-U.S. recovery efforts. It concludes with how the Barclays decision could economically boost future U.S. class actions, how the post-Morrison experience with non-U.S. recovery efforts reinforces arguments that foreign courts are not adequate alternative venues, and why courts should reject dismissals of such claims on forum non conveniens grounds.

In short, this analysis shows that it’s most fair and efficient to keep all parties and all claims in U.S. courts, rather than breaking up suits and sending claims around the world.

The Barclays Decision

In Barclays, the plaintiffs filed a class action in U.S. federal court alleging U.S. federal securities law claims on behalf of investors who purchased American depositary receipts (ADRs) traded on the New York Stock Exchange and U.K. securities law claims on behalf of those who purchased ordinary shares on the London Stock Exchange. U.S. institutional plaintiffs represented each class.

The court concluded that it had original jurisdiction under the diversity statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1332, and lacked discretion to decline it. The court rejected Barclays’ argument to dismiss the claims for forum non conveniens:

Because of this harsh result for plaintiffs, it is “an exceptional tool to be employed sparingly.” . . . To prevail, the defendant bears the burden of showing “(1) that there is an adequate alternative forum, and (2) that the balance of private and public interest factors favors dismissal.” . . . “The plaintiff’s choice of forum will not be disturbed unless the ‘private interest’ and ‘public interest’ factors strongly favor trial in the foreign country.”

Barclays, at *34–35 (emphasis added) (citations omitted)

Importantly, the court held that whether an adequate alternative forum exists must be judged against “the entire case and all parties” and not just the foreign law claims. Id. at *35. Concluding that U.K. courts were not a better forum but only an adequate one, the court went on to examine the private and public interest factors related to forum non conveniens.

It first considered seven private factors all related to forum convenience for the parties. The court noted that Barclays addressed four of the seven factors and conceded the remaining three. Specifically, Barclays operated internationally, many class members with U.K. law claims were likely domiciled in the U.S., and splitting the case into two proceedings would be less convenient for the parties, including Barclays, because the company would still need to defend the class claims remaining in U.S. federal court.

The court also noted that for financial wrongdoing like that alleged, the location of witnesses and evidence was less relevant—as evidence would likely be digital and easily transmitted electronically—and that Barclays would still need to make the same information available in the U.S. proceedings.

The court then evaluated five public factors, focused on the interests of each country’s court systems in resolving things. These included the local interest of suit, the court’s familiarity with governing law, burdens on local courts and juries, court congestion, and the costs of resolving disputes unrelated to the forum. To the extent these factors favored the U.K., the court held that they did not outweigh the private factors favoring its retention of jurisdiction and, further, that the plaintiff’s forum choice was not so “oppressive and vexatious” as “to be out of proportion to the plaintiff’s convenience.” Id. at *38 (citations omitted).

While thorough, the court’s conclusions are even more compelling considering 15 years of post-Morrison experience illustrating the challenges of non-U.S. recovery efforts.

The Recovery Landscapes

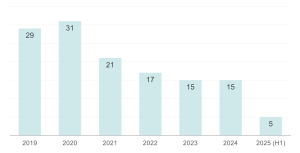

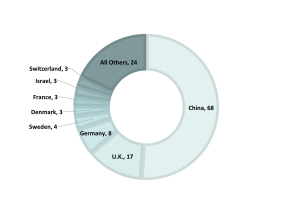

U.S. Class Actions with ADR Claims (2019–June 2025)

The following two charts show U.S. securities class actions against non-U.S. issuers from 2019 through mid-2025, grouped by country. Many more were sued during this time, but for this article, we have focused only on those that, like Barclays, included plaintiffs who held U.S. exchange-traded ADRs and had ordinary shares traded overseas.

|

|

|

Of the 133 suits, 39 settled, 54 were dismissed (9 voluntarily and 45 by courts), and 4 are ongoing. China is the most frequent country of domicile. However, issuers from other countries are well represented, including Brazil, Europe, Japan, and the U.K., all jurisdictions where we’ve seen many non-U.S. recovery efforts since Morrison.

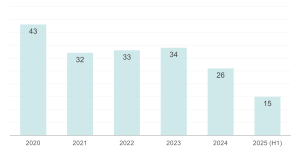

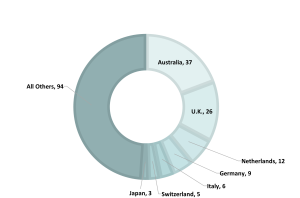

Non-U.S. Recovery Efforts (2020–June 2025)

For comparison, these next two charts show non-U.S. recovery efforts from 2020 through mid-2025, by issuer and country where suits were brought. Typically, these actions involve the issuers’ common or ordinary shares and were filed in countries where they were domiciled or had significant operations.

|

|

|

Only 18 companies were sued both in and outside the U.S. following the same scandals. Many companies sued in the U.S. are domiciled in countries like China, India, Russia, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates that do not offer viable private recourse for shareholder recoveries. Hence, we don’t see parallel claims there. Some issuers sued overseas did not have U.S. ADRs, which removed the option of U.S. suits. Even if issuers had U.S. exchange-traded ADRs, trading volumes may have been small, meaning class-wide damages would not have been sufficient to economically support a U.S. class action based solely on those claims.

Outside the U.S., regardless of country, recovery efforts are generally limited by the available routes to recovery. Some countries do not have defined shareholder causes of action. In Brazil, for example, there are questions about whether defrauded investors have legal standing to sue issuers and, if successful, the right to recover losses.

Even if remedies exist, most countries other than Australia and the Netherlands lack representative processes or they are less efficient than U.S. class actions. The majority require shareholders to pursue claims directly—individually or as a group. Doing so exposes investors to litigation risks and burdens, chilling participation.

Most countries outside the U.S. do not permit lawyers to represent clients on a contingency-fee basis. Instead, these actions proceed on a fully contingent basis only if litigation funders pay the lawyers and prosecution costs in return for a percentage of any success. However, funders don’t operate in many countries and, where they do, typically require claimant groups to have losses exceeding minimum threshold amounts as a precondition to proceeding. Bookbuilding is the process by which organizers (lawyers and funders) solicit investor participation to satisfy these thresholds.

These requirements—direct suits with associated risks and burdens, lengthy bookbuilding, and funder loss thresholds—can significantly reduce or eliminate non-U.S. efforts. If launched, they may not succeed. Post-Morrison litigation failures in some countries have significantly dampened funder willingness to finance cases (e.g., Germany and Brazil) and increased the cost of capital in others (e.g., the U.K.). Again, none of these systemic obstacles for suits exist when U.S. courts exercise supplemental jurisdiction over foreign law claims in U.S. securities class actions.

Boosting U.S. ADR Class Actions

The Barclays decision offers a boon for U.S. securities class actions involving U.S. exchange-traded instruments. In Barclays, the court did not compare the economic losses suffered by the U.S. ADR and ordinary share classes. Rather, it focused on the parties’ burdens in each forum, the overall fairness to both if it kept all claims, and the interests of each country in resolving things.

Because trading volumes are always greater, economic losses suffered by those purchasing ordinary shares on foreign exchanges will be much larger than for those buying U.S. ADRs. Therefore, including losses from ordinary share claims in U.S. ADR class actions will significantly boost potential recoveries, further motivating class counsel to include such claims.

Stay tuned for Part 2, which will take a closer look at how the Barclays decision could influence U.S. recovery opportunities moving forward.

Register below to watch Mike Lange’s fireside chat with BlackRock on ensuring class action remittance accuracy and oversight.